Table of Contents

Summer Institutes in Computational Social Science 2018 Post-mortem

Published on: August 19, 2018

We’ve just completed the 2018 Summer Institutes in Computational Social Science. The purpose of the Summer Institutes are to bring together graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, and beginning faculty interested in computational social science. The Summer Institutes are for both social scientists (broadly conceived) and data scientists (broadly conceived). In addition to the site at Duke University, which was organized by Chris Bail and Matt Salganik, there were also seven partner locations run by alumni of the 2017 Summer Institute:

- Hunter College (organizer: Maria Rodriguez)

- New York University (organizer: Adaner Usmani)

- Northwestern University (organizers: Kat Albrecht, Joshua Becker, and Jeremy Foote)

- University of Cape Town (organizer: Vissého Adjiwanou)

- University of Colorado (organizers: Brian Keegan and Allison Morgan)

- University of Helsinki (organizers: Matti Nelimarkka)

- University of Washington (organizers: Connor Gilroy and Bernease Herman)

The purpose of this post-mortem blog post is to describe a) what we did, b) what we think worked well, and c) what we will do differently next time. We hope that this document will be useful to other people organizing similar Summer Institutes, as well as people who are organizing partner locations for the 2019 Summer Institutes in Computational Social Science.

This post includes post-mortem reports from all of our locations in order to facilitate comparisons. As you will see, different sites did things differently, and think that this kind of customization was an important part of how we were successful. This post also includes a report from our traveling TA who visited five different sites.

You can read all reports or jump directly to the one that interests you the most: Duke University, Hunter College, New York University, Northwestern University, University of Cape Town, University of Colorado, University of Helsinki, University of Washington, and the traveling TA.

Duke University (Chris Bail and Matthew Salganik)

We’ve divided this post into five main sections: 1) outreach and application process; 2) pre-arrival; 3) first week; 4) second week; 5) post-departure.

Outreach and application process

Having a great pool of participants requires having a great pool of applicants. We took the following steps to spread the word about the Summer Institute:

- Posting announcements with professional associations

- Emailing participants from SICSS 2017

- Emailing visiting speakers from SICSS 2017

- Sending messages to email lists (e.g., polmeth, socnet, computational sociology)

- Emailing faculty that we thought might help us increase the diversity of the application pool

As far as we can tell, this outreach worked pretty well, but next year, we’d like to reach out more directly to groups that include folks that are under-represented in our applicant pool. We discussed this issue with the participants of the 2018 Summer Institute at Duke who are in the process of creating a directory of experts in computational social science that will make special effort to identify those from under-represented groups who we might approach to help us advertise the 2019 Summer Institutes.

In 2017 we received applications over email, and in 2018 we switched to a system based on Google Forms. This was a huge improvement because it helped the process run more smoothly and it reduced the amount of administrative work for us. The form used as the Duke site in 2018 is available at this link.

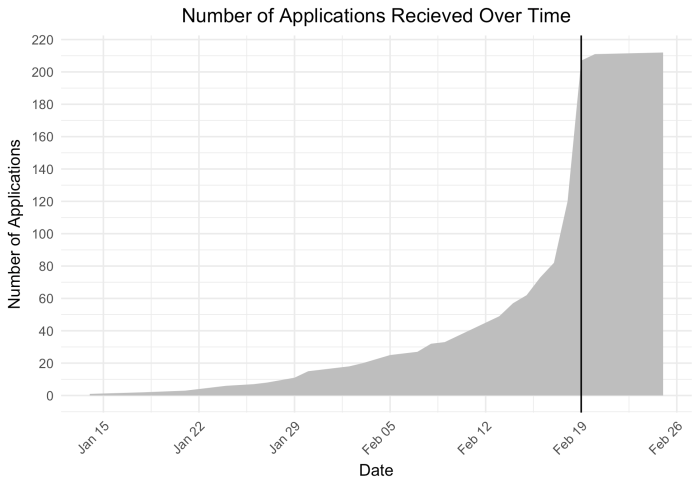

During the application process, we received questions over email. The most common question from 2017 was about eligibility so we made that more clear in the 2018 call for applications and the number of eligibility-related questions decreased. The most common question in 2018 was about the possibility of submitting a co-authored writing sample. So, we’ve made that more clear in the 2019 call for applications. We also had a number of questions about whether the application was received and/or whether we have made decisions. In 2019, we’d like to have a system that confirms that applications had been received and one that ensures that all applicants entered their email address correctly. In terms of timing, we found that most applicants arrive right before the deadline.

\

\

In order to select applicants, both organizers read all the files and then independently produced a rank list of 30 applicants. The organizers then exchanged lists and had a phone call one week later. During the phone call, the organizers quickly discussed the candidates who were in both of the top 30 lists and the candidates who not in either top 30 list. Most of the time, however, was spent discussing applicants that were on the list of one organizer but not the other. When deciding which of these candidates to admit, we took into consideration not just each person individually, but also the composition of the participant population as a whole. This process is time consuming, but we are not planning any changes.

Finally, looking ahead to 2019, we’ve adjusted the language in the call for applications to encourage more applicants from a wider range of backgrounds.

Pre-arrival

After admissions, which ended in mid-March, we sent admitted participants materials to help them get ready for their arrival. This year we encouraged participants with less background in coding to complete some modules on DataCamp. We were able to make all the DataCamp materials available for free to all participants through the DataCamp for the Classroom program. We found that some participants did take advantage of DataCamp. One thing we can do better next year is to get the DataCamp subscription for participants sooner. Also, in our communication with participants, next year we plan to separate some of the intellectual pre-arrival activities, such DataCamp, from the logistical pre-arrival activities, such as information about housing.

When sending students access to DataCamp, we also created a Slack for participants to access the TAs during office hours. Next year, this office hours Slack should be called “Participants, SICSS 2019” and it should be used by all participants at all locations before, during and after the Summer Institute. We found that this single Slack helped encourage some cross-location interaction during the Summer Institute. As with this year, we also plan to have a separate Slack for all organizers in all locations. In general, however, we believe it is important to minimize the overall number of Slack workspaces associated with the Summer Institutes in order to minimize confusion about where conversations should take place (both among organizers and participants).

Another important pre-arrival activity we initiated this year was to have students submit photos and bios for the website. We did not do this in 2017, but it was suggested by several of our participants during the 2017 event. According to participants of the 2018 Summer Institute at Duke, this helped create community during the first few days. We will do this again in 2019, and we will encourage all partner locations to also post participant bios before everyone arrives (this year, most of the partner sites waited to add bios and pictures until the first few days of their events).

The teaching model that we use requires all participants to bring a laptop. This has not been a problem yet, but it is important to make this clear to participants before they arrive. Further, efforts should be made to create accommodations for participants that don’t have laptops. In our 2019 email to admitted students, we will note that students who do not have access to a laptop can request our help in arranging to borrow one during the Institute.

In terms of “behind the scenes” logistics, as much as possible should be done before participants arrive. This year we ordered t-shirts for people at all the locations. This was great for community building, but it was logistically difficult because we did not have access to the roster of participants at each institute and because shipping costs to several of our institutes were prohibitively expensive. In 2019, we plan to have all the gifts for participants at each partner location before the Summer Institute begins. We think that mugs might be a good choice because there are no issues with sizes.

As with 2017, in 2018 we used a professional technician for livestreaming and audio-visual services at Duke University. This was a bit expensive, but we think it was worth it given that so many people were watching lectures from the Duke event at partner locations. One improvement that we made in 2018, was having a dedicated laptop used for all presentations. This meant that all the organizers and TAs had access to their own laptops during the entire event. When necessary, slides or other materials were sent via Slack to this laptop.

Finally, in terms of physical space, the room that we used in 2018 worked well, but it lacked two things: a clock and whiteboards for participant work. In both 2017 and 2018, our room had a flat floor with configurable furniture. We recommend this kind of room for partner locations. A bowl classroom with fixed, individual seats is not ideal for group work.

In terms of dividing up the work among organizers, most of the pre-arrival work was modular and fell into one of these categories: Slack, DataCamp, getting participant bios on the website, A/V, housing, food, and visiting speakers.

First week: classes

Most days of the first week of the Summer Institute followed the same general pattern: lectures in the morning, lunch, group activity, feedback, visiting speaker, and then dinner. Many participants—and organizers—felt a bit overwhelmed with everything that was happening; someone described the Summer Institute as drinking from a firehose. But, we think that 2018 was smoother than 2017, and we think that 2019 could be even smoother.

The biggest question by far about this first week this year was how it would work with the partner locations. Fortunately, we think it worked very well.

We posted all slides and annotated code associated with each morning lecture to the website before teaching so that folks at the partner locations could follow along on the slides if they wished. We also had a seperate Slack channel to take questions from partner locations, and we had a TA who was responsible for monitoring this slack channel and asking these questions. This process worked well. We also posted all the materials needed for the group activity to the website, and we provided background information to the location organizers through our organizer Slack. Next year, it would be helpful if we could post the teaching materials and group exercises earlier so that they organizers of partner sites could adapt them to their local audiences as necessary or otherwise prepare for the exercises with their TAs.

There are a four main logistical complexities added by working with partner sites, but these are fairly minor. First, we needed to ensure that we had high quality A/V for the livestream. Second, we needed to ensure that the lecture videos are posted to YouTube very quickly for the partner locations in different timezones. For example, the partner locations in Cape Town, Helsinki, and Seattle all watched some of the videos on YouTube. Third, we needed to have a TA monitoring Slack to ask questions that come from participants at the partner sites. Fourth, we needed to be sure to stay on schedule. We also sought to avoid last minute changes to the schedule, though we did dedicate the first 15 minutes of each morning to discuss local logistics with participants (often these discussions involved issues related to accommodations or food).

After the morning lecture and lunch, students worked on an activity that was designed to practice the material covered in the lecture. Each day we randomly put participants into 5 different groups of about 6 people each. Participants enjoyed having a chance to work in mixed groups, and this provided folks a chance to work together some before the group research projects in week 2 (more on that below). For next year, we might slightly increase the number of groups, which would slightly decrease the size of each group. Also, we might do a bit more work to ensure that the groups are balanced.

About 30 minutes before the visiting speaker, we brought everyone back together for a debriefing about the activity. This debriefing was helpful for the participants to see common themes that emerged across multiple groups. The activities generally worked well, but we rarely had enough time to finish them. This was frustrating to participants, but it is hard to design open-ended activities that can be finished on a specific schedule. Next year, we will try to provide more context so that participants don’t expect to finish. Also, we can further shorten the lectures and start more of the activities before lunch.

After debriefing the group activities, participants did a quick keep-start-stop survey through Google Forms. This means that participants describe the activities they want us to keep, the new activities they want us to start, and the activities they are not enjoying. Then, the next morning (during the 15 minutes dedicated to logistics) we gave feedback on the feedback, reporting what was said, what we changed, and what we decided not to change. We think this feedback and feedback-on-the-feedback process was very helpful in the first few days. We will use it again next year, and we would strongly recommend that partner locations use it as well.

Most days, starting at 4pm a visiting speaker would present his or her research. During this time, participants at the partner locations could ask questions through Slack (again with one TA monitoring and speaking up). In addition to questions during the presentation, we also organized two other ways that the visiting speakers and participants could interact. First, during the afternoon before the presentation, participants could sign up to meet with the speaker for 30 minutes. We generally had more sign-ups than time spots, so participants would often meet with speakers in small groups. Second, we invited the speaker to join us for dinner afterwards. We found that both of these activities worked well. In terms of logistics, this year we had one TA who was in charge of the afternoon meetings: scheduling them and keeping them running smoothly. Have one person totally focused on facilitating these meetings was a big improvement over last year, when the meeting were a bit chaotic. One of the visiting speakers recommended that we consider having one-on-one meetings after the visiting speaker’s lectures so that the content of the talks could be discussed- though this would be nice, it introduces a number of logistical challenges related to travel of the visiting faculty members.

There are four other things that happened during the first week that we think helped build community, all of which we will do in the future. First, we had a very informal opening dinner that briefly introduced the Institute at Duke and prepared participants to introduce themselves to each other in a more formal manner during the following (first) morning. Second, during the week, we had participants write name cards that they put on their desk and we had them wear name tags. Third, participants from all the sites had access to a common Slack, and we found that during lectures they would share link and ask and answer questions there. We observed students from multiple partner institutes helping each other on the Slack channel on numerous occasions. Fourth, we started a system for discussion tables at meals. There were often topics that came up during the lecture or group activity debrief that participants want to continue talking about, so we decided that any participant could conveen a discussion table by writing the topic and their name on a white board near the door. We found that this process worked well logisticall and created more participant-driven learning, which is something we are trying to do more. Here’s a list of discussion tables that took place:

- Ethics of screen scraping

- Working with companies

- Diversity in computational social science

- Description vs prediction vs causal inference

- Ethics of algorithmic decision making

- Null effects

- Partner locations for SICSS

- Teaching computational social science

- Publishing in computational social science

Second week: group projects

During the second week, participants worked on group research projects. The goal was that some of these projects would eventually turn into published research in computational social science. On Monday morning Chris led an intellectual speed dating process. This process involves first crowdosurcing a list of research interests, then having students place 1s or 0s next to the items that are of interest to them. We then run a cluster analysis to identify maximally similar and dissimilar groups. Students meet in each of these two types of groups for 30 minutes in order to come up with possible research topics. These topics are then added to a google spreadsheet and participants were asked in early Monday afternoon to write their name next to the project they would like to join. This process was smoother in 2018 than in 2017 in part because we did a better job of telling students about the group projects during the first week.

In order to create some moments of shared activity during the second, we also had flash talks by participants. These generally took place at lunch time and were 15 minutes long: 10 minutes to present and 5 minutes for Q & A. These flash talks were a mix of presentations about research and useful tools (e.g., open source software). A full list of the flash talks is provided on the Summer Institute schedule. The flash talks were a success and we plan to continue them in future years.

In order to support the group research projects, organizers and TAs would circulate between the groups offering advice. We also provided small grants to groups that needed them. This grant process was not very smooth this year, and we think participants spent more time thinking about it than was necessary or useful. Here’s a proposed system for next year. During the Summer Institute it should be very easy to get a micro grant (hundreds of dollars) to run a quick, proof-of-concept pilot. Then, participants could build toward a full grant proposal submitted a few weeks after the Summer Institute. To receive a micro grant, participants could submit a one paragraph description of what they want to do and why at lunch time each day. Then, the organizers should be able to provide an answer by dinner time, if not before. Participants can create a special email account for their project, and this email address can be used to create an account with the service provider (e.g., Amazon Mechanical Turk) and money can be deposited into this clean, new account. This system requires creating new accounts, but it avoids any accidental comingling of projects. We also plan to spend more time clarifying the scope and purpose of the group project during the final session on Saturday morning– in particular, we want to communicate that the participants are not expected to produce a polished research project by the end of the week, but rather a strong research proposal (or a proposal to create infrastructure of other tools that will help expand the field).

During the second week we also had two guest speakers present remotely. In terms of logistics, one of these went smoothly and the other had poor audio and video quality. For speakers presenting remotely in future years, we should try to get slides ahead of time, and we should test the entire set-up. This would help us find problems with the software or internet connection (or both). This year we tended to use free services such as Google Hangouts and Skype. In future years, we could try one of the many paid video conferencing services.

On Friday afternoon participants presented their group research projects right before the closing dinner. We think that participants benefited from seeing the presentations of the other groups, and it provided us a chance to ask some questions that connected the specific projects to the more general themes of the Summer Institute. Next year, we will begin these presentations slightly earlier in order to facilitate final group meetings where the participants can discuss the next steps for their projects while they are together in person.

The most common problem during the second week was that some of the group research projects would struggle to get started or would get stuck. Some of this should be expected when there are people from different fields trying to work quickly on a new project. But, we did have a few strategies for trying to get the groups moving forward. First, we tried to remind participants about disciplinary differences in research goals; some of being stuck was just people not understanding each other. Second, we tried to turn a disagreement into a research question. For example, if one participants want to use data from Yelp and one wanted to use data from Google Places, we suggested that they use both and compare the results. Third, we sometimes tried to lower the stakes. That is, some of the times that groups got stuck, it felt like some of the participants were viewing this as something with very high stakes. We were reminded everyone that they can just think about this as a learning experience, it seemed to help people try new things. Finally, if a group was stuck, we also encouraged them to consider switching teams. Overall, we think that a huge amount of learning happens during the group research projects, but everyone should remember that trying to do interdisciplinary group research projects in a week is difficult.

Finally, we would make one small logistics change next year: we don’t think it is a good idea to schedule a visiting speaker the night before the group research projects are due.

Post-departure

After everyone has left, there are a number of things that need to be done to archive what happened this year and to prepare for next year. These wrap-up activities include: archiving all slides, code, data, and videos; collecting evaluations from participants; reviewing and funding research grant proposal; thanking speakers; creating ways to stay in touch (e.g., Facebook groups); and planning a meet-up. Also, final book-keeping of expenses related to the event should be conducted promptly so as to come up with a final estimate of the amount of money available to participants for research via post-Institute grant proposals.

Hunter College (Maria Rodriguez)

The Silberman School of Social Work, part of Hunter College at the City University of New York (CUNY) hosted a satellite SiCSS site from June 18th – July 29th, 2018. Student feedback indicates the institute was extremely successful in its first implementation, and there was a unanimous call for a bigger, better institute to be hosted in 2019. This post-mortem is organized chronologically, beginning with the application process and ending with student feedback. The final section offers the main organizer’s reflections concerning institute strengths and deltas.

Applications

Hunter SiCSS was organized as a domain specific site, and was further limited due to main organizer time constraints. As such, applications were open only to CUNY affiliated graduate students and faculty. We had 8 applicants (and an additional 3 queries from other prospective students) and accepted 8. A copy of the application can be found at the Hunter SiCSS site: https://compsocialscience.github.io/summer-institute/2018/hunter-nyc/apply.

General Event Organizing

The students were comprised of 5 current CUNY doctoral students (all Silberman affiliated), 1 junior faculty member, 1 senior faculty member, and 1 MSW student. CUNY does not have dormitories, thus we were unable to offering lodging to any students: however, all were already NYC/NY area residents and did not require lodging. We organized Breakfast and lunch for all days during week 1, and the first and last day of week 2. We asked folx if they required any additional assistance to realize their full participation and only came across one issue: one participant had an ancient computer that ultimately couldn’t perform some of the more intensive computations. We resolved it by loaning them a laptop during the morning lectures, and partnering the participant up with others during the afternoon exercises.

Week 1

Nearly all participants had little to no exposure to programming beforehand. As such, we structured our week 1 days a bit differently than main site SiCSS. Afternoons during days 1-3 were focused on learning basic R interfacing: understanding where the idea for R came from, Rstudio, version control with git/gitub/rstudio projects, and doing basic analysis with R. Students reported this was a very useful part of the institute because it gave them a solid foundation from which to dive into the Day 3 group activity and beyond.

Week 2

Because of the nature of commuting in NYC, we adjusted our schedule so that we 1) did not meet during the weekend and 2) met via Slack during Tuesday-Thursday of week 2. Students reported this schedule to be most helpful, since some commuted from as far away as Baltimore.

Though the application asked participants to commit to all mandatory institute days, and made the three middle days of week 2 optional, we still had 3 students who did not participate in the final day of presentations. This attrition was due to work and school obligations. I don’t know that there is a direct way to address this, as I note other sites had similar issues. Perhaps it may be best to accept more students to account for a small percentage dropping out?

Final projects were predominantly individual, though there was 1 two-person group. Importantly, we had an intergenerational presentation day with 2 children of students (ages 5 months and 15 years old) joining us on the last day. The 15 year old actually served as his dad’s TA and gave a small portion of the final presentation – it was pretty cool.

Main Organizer Reflection

Below is a summary of the strengths and deltas of the Hunter SiCSS site form the main organizer’s perspective.

Key Strengths

Disciplinary Homogeneity

Students noted that having a roomful of social works tackling an area of inquiry that excited them but currently has little exposure within the field was immensely inspiring and affirming for their own desire to pursue these methods and data within their own scholarship. My main goal for this institute was to begin to build a body of computational social worker scientists, and that seems to have begun taking shape.

Small Group Size

Though the number of students was small, the size was useful in two ways. One, as a junior faculty member, I wanted to experience running the institute with a smaller pool to understand what the challenges and opportunities were and in order to not take on too much too fast. Second, students reported a quicker sense of camaraderie amongst each other and thus were better able to learn from each other during the group exercises.

Focus on the Basics

Recognizing the limited exposure to programming, it seemed appropriate to provide incentive and justification for the use of R/Rstudio (to say nothing of Python) for research and, in the end, was a key piece of the institute that students reported appreciating the most.

Emergent Design

Each day ended with a 30 minute debrief in which participants described what went well, what was challenging, and how they wanted to carry over themes into the next day. As a result, each day was altered slightly to accommodate student demand and this worked well to maximize learning.

Main Deltas

Datacamp

There was uneven uptake of the Datacamp lessons, despite multiple email reminders. Student feedback was that the emails used the term “suggested’ and future institutes should be clear that these are mandatory. Further, it was unclear that main site TAs were available to support students from other sites during the lead up to the institute with programming. Having clear main site TA availability denoted in a more prominent way and making clear DataCamp is required for all novice programmers would likely go a long way toward increasing the use of Datacamp for novice programmers prior to SiCSS.

Slack

Students reported using Slack during week 1 was cumbersome, generally as a result of having to split attention between the computer and the lecture. There was no exposure to Slack before the institute, and I wonder if there is a way to present it earlier in the application/acceptance process to help gain some facility.

Disciplinary Homogeneity

While inviting participants only from social work was a strength, it’s also something I’d like to change for two reasons. One, student feedback indicated that having more computer science/programming expertise beyond the TAs and main organizer would have been extremely beneficial. Second, during the institute Matt summarized Sociology as the study of groups of people. Social Work is the study what happens when people are excluded from the group AND mitigating the impacts of that exclusion for BOTH groups. Social Work is applied sociology, yet this is little understood or described. Thus, the second reason I’d like to expand the applicant pool is to increase exposure for social work scholarship and theory as a matter of import for creating social science for social good.

Mturk

Unfortunately, we didn’t have anyone who wanted to engage with the Mturk group exercise, but I believe I should have made it mandatory, if nothing else than to show what is possible and not with it. Social Work is a population specific field of inquiry, and students felt that Mturk may not be useful in social work inquiry, so I’ll need to think about ways to argue for its (albeit limited) use.

Application timeline

The application didn’t go live until early-mid May, which was not ideal. February/March would have been preferable to garner more applications.

New York University (Adaner Usmani)

I declare the Summer Institute for Computational Social Science at NYU a great success. To be sure, the week was not without its hiccups. There are many things that could have been done to improve it. Next year will no doubt be better. But none of my worst fears were realized, and the feedback from attendees was overwhelmingly positive. Below I summarize the week’s events, what went well, and what could be done better next time around.

What Happened

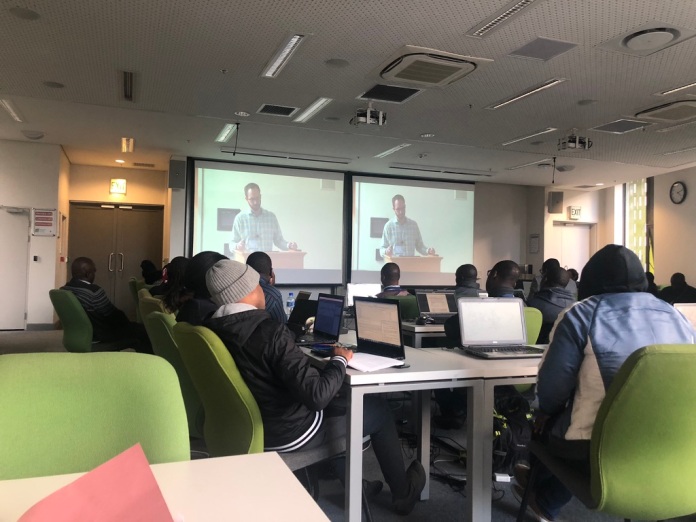

About 20 graduate students and a couple of postdocs attended SICSS 2018 for the first week of lectures and activities. We met in the main seminar room of the NYU Sociology department from 9:00am to 5:30pm. The mornings were devoted to lectures by Matt Salganik and Chris Bail, beamed live from Duke by projector; the afternoons were devoted to group activities building on the morning’s material, conceived by SICSS HQ at Duke and supervised by Barum Park and myself, Adaner Usmani (and on Monday and Tuesday by Taylor Brown, the global TA).

We had planned to continue the institute remotely, during Week 2. Indeed, on the final day of the first week, participants organized themselves into five groups each working on different projects. They expressed considerable enthusiasm about making use of the funds allotted to these research projects. The plan was to work via Slack and then share some kind of deliverable with me (and SICSS HQ) by the end of the second week. Unfortunately, not all of this energy came to fruition. One group made progress, but they did not spend anything like the allotted amount of money. Other groups have plans to spend more of their allotted money in the near future, all of which should be available to them through NYU for a while. But the second week lacked the coherence and energy of the first week, which was unlike the experience that I had at SICSS 2017. Below I reflect on why this happened.

What Went Well

My main goal in conducting the partner location at NYU Sociology was to expose graduate students who would not otherwise get any training in Computational Social Science. The goal, to be clear, was not exactly to train these students. In my view, that takes more time and effort than one week would ever permit. Rather, it was to introduce them to new methods and ways to learn these new methods that will, at some point, stand them in better stead. Put another way, the real purpose of the institute was make unknown unknowns into knowable knowns. In this aim, the week totally exceeded my expectations.

When I conceived doing something like this last summer, my target audience was 5-10 NYU Sociology students. As it happened, these 5-10 students attended, but so did 15 people from other disciplines and institutions who were similarly keen to learn what their grad programs were not yet able to teach them. Note that all of these people were largely recruited despite my advertising efforts, not because of them — because I anticipated constraints on space, I did not advertise beyond the NYU Sociology department. My sense, then, is that there is enormous demand for what SICSS NYU did. The fact that we served this demand competently and for a large number of people makes me proud to have been associated with the inaugural NYU satellite.

What else went well? The lectures were excellent — not just the material, but also the logistics involved in screening them. The livestream was always of excellent quality and the SICSS-wide Slack enabled participants at NYU to ask the speakers and each other questions. In their evaluations all participants remarked on the quality of the lectures. Similarly, the afternoon activities were very useful: they were digestible, well-conceived, and exciting. Every afternoon, the NYU Sociology conference room was buzzing with activity, which was very fun to watch.

One of the dividends of attending the inaugural SICSS at Princeton was that I met (and remain friends with) a number of people with whom I share methodological and substantive interests. In my estimation, SICSS NYU has done the same for those that attended. I was not sure that this was going to be the case, on Day 1. I had not established any kind of barrier to entry except affiliation to an academic institution, which meant that I did not curate the pool of attendees at all. I worried that the interests of those attending were too diverse and their skill-sets too incommensurate. But I no longer worried about this on Day 6. In the final analysis, SICSS NYU put a lot of interesting, motivated social scientists in touch with a lot of other interesting and motivated social scientists. This camaraderie was greatly facilitated by the group activities [1].

[1] Two things we did well that improved the group exercises, in my view: (1) we surveyed attendees about their prior R experience, and stratified the randomization process based on these categories; (2) we varied the size of groups from day-to-day. I would encourage future organizers to follow suit.

What Could Be Better

Of course, while there were many successes, there were invariably many challenges. Many of these admit of easy improvement. Here I discuss the main things that might be done differently, in the future. These are roughly ordered from least to most difficult to implement.

Logistics

There were a handful of logistical snafu’s — concentrated on the first day, but peppered throughout the first week — that are probably unavoidable parts of the inaugural edition of something like this, but which are easily addressed.

First, at 9am on the first morning, it had not occurred to us that attendees would need Wifi. NYU makes it difficult but possible for guests to access Wifi, so this took 15 minutes to organize. Future organizers should remember that everyone needs Wifi access.

Second, by 12pm on the first day, it became clear that we had 25 laptops in the conference room but not space for 25 power chargers. This was easily remedied by the next day with a trip to CVS, but it would be better to plan for this in advance.

Livestreaming

While the livestream from the main institute was crystal-clear, our own livestreaming capabilities were remedial. Being in NYC, we had access to an excellent list of guest speakers. But other institutes were not able to profit, as our video was grainy the audio terrible. This was a disappointment, but one that I did not have the bandwidth to address during the institute itself. Next time I would suggest that future organizers spend some of the grant money on livestreaming equipment. Even minimal investment ($250-$500) would yield enormous rewards in image and sound quality.

Attendee Preparation

The main challenge in the group exercises came from the distribution of attendee experience. Two facts about this distribution were challenging.

First, there was wide unevenness in prior R experience. We tried to address this problem by stratifying the groups and making sure that there was at least one person with significant R competence in each group [2]. But invariably the unevenness of R abilities meant that group dynamics were a function of the compassion shown by the most competent coder — if the most competent coder was impatient or more interested in learning the skill themselves than teaching it (which we tried to discourage but could not effectively police), the group exercise was not useful for those without much coding experience.

Second, the median of the distribution of abilities was low — lower than I had anticipated (lower than the distribution at SICSS Princeton 2017). This meant that most groups made little progress in these group exercises.

In my view, there are two ways to address this problem.

First, we could tailor the group exercises to different ability levels. Those without much coding experience might learn much more if they worked alongside those of similar abilities on a less difficult coding task than if they are stuck watching over the shoulders of a not-so-compassionate, experienced R user.

Granted, this would probably not work for those who have zero R experience whatsoever. Given this, I think it is imperative that future organizers also try to compress and shift upwards the distribution of attendee skills. This could be done by making the DataCamp courses mandatory or even just strongly emphasizing them in pre-institute communication. I regret not doing this.

[2] We were also fortunate that Barum Park, our superb teaching assistant, was an excellent user of R and was able to go from group-to-group to help.

Attrition After Week 1

Week 1 went very well, but Week 2 less so. Throughout Week 1, I reminded attendees that they had $2500 in research funds to use. On the last day, they formed five different research groups, each planning to work remotely via Slack. I asked that by the end of the second week they submit some kind of short deliverable (presentation slides, a description of the research they did, etc.). Yet as of my drafting this report (around 10 days after the end of the second week), only one group has submitted a summary of their research (and they spent only $50). I guess that up to $500-$1000 more of this money will probably be spent, but it is very unlikely that we will use the whole $2500.

Why did the second week lack the focus and coherence of the first? The principal reason is that we did not hold the second week on-site. When I first conceived SICSS NYU, I thought that the satellites were only going to be one week long, so I had planned to fly out of NYC at the end of the first week. As it turned out, I am aware that some of the other satellites met into the second week with great success. Thus, if future organizers are keen to see attendees work on research projects, I would urge them to budget the full two weeks and to ask their participants to commit to being on-site for both weeks. In retrospect, it was too difficult to ask attendees to coordinate research projects over Slack in just one short week.

In my view, this experience raises some questions about the structure of and funding for the satellites. There were several students at SICSS NYU 2018 who probably would not have attended if I had asked that they commit to being at NYU for two consecutive weeks. How should we deal with this class of applicants? One possibility would be to admit only those who can stay on-site for two weeks. Another possibility would be to admit two kinds of students: those who stay for one week, and those who stay for two. Only the latter set would be eligible to apply for research funds through SICSS. This is the model I would prefer. A third possibility would be to have some satellite institutes that meet just for one week, and others that meet for two. In any case, I do not believe it makes sense to transfer research funds from SICSS HQ to those institutes that meet on-site for just one week, as our experience suggests that much of this money will go to waste. Much of the SICSS money that was transferred to SICSS NYU 2018 for this purpose lies unused.

Attrition Before Week 1

While 20 people attended SICSS NYU for the full week, I had expected (and made plans for) about 30 people. About half of these people pulled out in the weeks prior to the start-date, and about half in the few days leading up to the institute. Had I known the exact numbers earlier, we could have saved some money on catering. Future institutes may be able to put this money to use, so it is worth considering whether this kind of attrition can be stemmed.

My guess is that this attrition was a result of the fact that participants who signed up for SICSS NYU did not have to offer anything beyond a verbal commitment of their time (unlike some other satellites, we had no formal application). While I emphasized that they were expected to attend if they signed up, there was no way for me to enforce this rule. If my guess is right, future organizers might consider increasing the costs of applying by requiring a formal application [3]. I would expect the experience of submitting a formal application to reduce this kind of attrition.

[3] One could still accept all applicants, of course, thereby preserving the accessibility of the SICSS partner locations.

Guest Lectures

Guest lectures at SICSS NYU 2018 went well, overall, but there was not enough communication with the guest speakers about the content of the summer institute and the background of our audience. This was particularly an issue at SICSS NYU because we had our most advanced lecture on the first afternoon (Monday), before many participants had even been introduced to CSS. It may not be easy to address this, since speaker availability greatly governs the timing of guest lectures. But at the very least, I would recommend not scheduling a speaker on Monday, and trying to build from the simple to the complex — if possible.

Organization

About half of the respondents found the day’s schedule too packed, even though we let participants go by 5pm (i.e., we didn’t have group dinners, as we did at SICSS Princeton 2017). This may be because lectures were live streamed. It is tiring to listen to lectures in-person, no matter how excellent they are. But I venture that it is even more tiring to listen to lectures over a live stream. I do not have a good explanation for it, but I do have small-sample evidence that it might be true [4].

If this is true, there are two things that future organizers might consider doing. First, we could cut the number of guest lectures. By 4pm, attendees were tired, but they were not exhausted, as they were by 5:30pm. Simply reducing the amount of time spent sitting and listening to lectures might be sufficient.

Second, more ambitiously, SICSS HQ might consider abridging some of the lectures, as was suggested by some respondents to our post-institute survey. Particularly now that past lectures are all archived, attendees of SICSS 2019 could be required to watch some of the past lectures before attending, thus freeing up time during the week.

[4] That is, I refer to a comparison of my estimate of attendees’ tiredness during SICSS 2017 and my estimate of attendees’ tiredness during SICSS NYU 2018. Of course, there are confounders. The most significant confounder is that SICSS NYU 2018 was held in a poorly-ventilated windowless room, whereas SICSS 2017 had windows and much better ventilation.

Northwestern University (Kat Albrecht, Joshua Becker, and Jeremy Foote)

This post-mortem uses the “strengths and challenges” approach to feedback. Strengths reflect practices that worked well, and challenges reflect practices that can be improved. For both strengths and challenges, associated strategies are brainstormed to indicate how the strength can be harnessed or the challenge can be addressed.

These points are not listed in any particular order.

Strengths

- Several participants remarked that the rooms were nice. In addition to providing a large and inviting main room, the building offered a large variety of workspaces for group projects. Strategy: If we move, ensure that facility is nice.

- The food was plentiful and good. Strategy: If we move to another location, ensure food is good.

- Participants appreciated the online material and found it very useful, including the slides, Chris’s code, and the modeling resources. We encouraged participants to read exercises a day in advance, which helped them to prepare. Strategy: We can be stronger on this point by making all materials available prior to start of institute. We could go through available materials on day 1 logistics.

- In participant feedback, several members indicated an appreciation for the exposure to a broad array of topics within computational social science. Strategy: We can increase the breadth of coverage by maintain or even grow coverage of experiments & modeling, which is currently an underrepresented area of the curriculum: SICSS-Chicago devoted 1 day to ethics, 3 days to observational methods, and 1 day to combine both formal modeling and experimental methods. However, increase of breadth necessarily comes at the expense of depth.

- Having the least experienced person in each group code during daily group exercises encouraged collaboration and helped people learn new skills. Strategy: Keep doing this.

- Having the central site take questions for guest speakers over slack greatly enhanced the feeling of cross-site participation. Strategy: Keep doing this and seek additional opportunities for cross-site participation, such as encouraging cross-site projects. This might also address some of the challenges with group formation where people are interested in a project but can’t find enough people to work with them.

- Having local speakers, gave the Chicago partner site a unique sense of locality and helped to promote the goal of building CSS community in the Chicago area. This approach justified the framing of the SICSS-Chicago partner site as more than just a geographical convenience for people who wanted to participated. Strategy: Utilize these resources more by allocating more time in the schedule for their visits, e.g. planning lunch/meeting sessions with all guest speakers.

Challenges

- People wanted name cards/tents. Strategy: Get name cards/tents.

- People shared concerns that the institute was not equally accessible to social scientists and computer scientists–specifically, that people with no social science skills could easily complete the institute, while people with no computer science skills struggled. Strategy: Spend some more time talking about social science. Place clearly the role of social science in this process. For example, without good theory, you cannot develop a good research question. This point tends to become clear during the second week when people are working on group projects.

- People felt underprepared computationally. In particular, people found they were not able to complete the group exercises during the first week. Strategy: We think the best strategy here is to better manage expectations around computational skills. One important strategy for this is to more loudly signal the expectation that people will use Datacamp to prepare themselves computationally, to encourage people to prepare more thoroughly and enter the institute with stronger skills. Another strategy is to manage expectations around what is possible in a short period of time, namely giving people the expectation that, as new coders, a lot of time will be spent wrangling data, waiting for things to load, and troubleshooting simple issues—and that this is not failure, but learning.

- There were very few participants with strong computational skills, as compared to the number of participants with strong social theory skills. Solution: Recognizing that recruitment for SICSS-Chicago 2018 reflected our social network, we need to work intentionally to Increase recruitment efforts among computer-science disciplines to identify computer scientists interested in social science.

- Not enough time was allocated to complete the daily group exercises. Strategy: We don’t have a clear path forward to address this challenge, as the successful strategy depends on several factors. If future location and funding supports it, one option is to provide dinner as well as breakfast/lunch to enable longer working days. Another option, if the resources support a second week of meals, is to host local speakers during the second week so they’re not competing on the schedule with syllabus materials and guest speakers from the central site. An additional strategy, regardless of resources, is to frame expectations around the possibility that participants can/should continue working on exercises even after the day is officially over—especially in the spirit of self-teaching, and the idea that you get out what you put in.

- Overall, the schedule felt crunched due to the fact that we added local speakers to the schedule on top of the existing material for the first week. Strategy: As mentioned above, one strategy is to find resources to support a second on-site week (i.e., with meals). Another option is to start at 8am every day, but this of course poses a challenge for people commuting from across town. We chose not to replace livestreamed speakers with local speakers.

- The limited availability of support for people coming from outside Chicago generated some negative feedback from people who traveled for the institute. Strategy: There are three potential strategies to meet this challenge: (1) Get more funding to support travel & loging, (2) restrict participation to Chicago-only people, (3) more assertively signal that this institute is intended for Chicago area participants, and as such there should be no expectation that we can support travelers.

- There were not enough breaks in the schedule. Strategy: In addition to the strategies mentioned elsewhere for reducing the load during the week, we can also schedule more breaks.

- People had difficulty collaborating on group projects while each using individual computers. Strategy: We can proactively provide tips on collaborative tools, such as Colaboratory, and encourage the use of standard tools such as Dropbox and Google Drive.

- People’s final project groups were highly correlated to their geographical location within the room, despite starting the week with a “research speed dating” and running mixer activities throughout the week. Strategy: Include one final mixer activity during the final group formation process.

University of Cape Town (Vissého Adjiwanou)

The Summer Institute in Computational Social Science (SICSS) held a two-week training workshop from June 18 to June 29 at the University of Cape Town, run by Dr. Vissého Adjiwanou, Senior Lecturer in Demography and Quantitative Methods at the Center for Actuarial Research (CARe) at the University of Cape Town (UCT) [1] and the chair of the Scientific Panel on Computational Social Science at the Union for African Population Studies (UAPS). This year’s Summer Institute is an institutional collaboration with the main site at the Duke University and six other sites in the US and Finland. The Cape Town workshop has provided African scholars and students from various disciplines the opportunity to learn new quantitative methodologies related to digital trace data and to hone their research capabilities.

The Summer Institute in Cape Town has adopted a dual teaching approach which combined livestream lectures from Duke University with onsite presentations. During the two weeks of the Summer Institute, several lectures and talks were given by experts in the field of Computational Social Science. At the opening, Vissého Adjiwanou presented the importance of the Summer Institute for African scholars and led discussions on issues about estimating about causality in Social Science, and considered how new methods and data can contribute to a better understanding of social phenomena in sub-Saharan Africa. The lectures given at the SICSS then covered topics ranging from ethics, surveys and experiments in the digital age, by Matthew Salganik, to digital trace data collection and analysis (text analysis, topic modeling and network analysis) by Chris Bail. 2 by livestream from Duke University. Due to the six-hour time difference between Cape Town and Duke University, participants in Cape Town were unable to listen directly to the guest speakers at Duke University but watched recorded versions. The videos of these talks are freely available online to participants.

Onsite in Cape Town, the participants attended various lectures and talks on diverse topics. Nick Feamster delivered a lecture on machine learning and its application to detect ”fake news” from the web. Marshini Chetty gave a talk on ethics and on human-computer interaction. Tom Moultrie (director of CARe) introduced the participants to the opportunities provided by Computational Social Science for monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals and presented some challenges with working with digital trace data. Marivate Vukosi from The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) spoke of how data science should be used for public good. He presented various research projects he conducts in the field from road security to safety and crime incident detection on social media. The Summer Institute has also benefited from the participation of Kim Ingle from the Southern Africa Labor and Development research Unit (SALDRU) at UCT who introduced the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) to the participants. Finally, by Skype, Ridhi Kashyap, associate professor of social demography at the University of Oxford, presented her work on sex selection in India using Facebook Data. These various and highly qualitative research presentation made the Summer Institute one of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa, where participants learned from specialists from Africa and around the world.

In the second week, the participants worked in five small groups on various applied project, and they presented their results on the last day of the Institute. The first group worked to map research on gender based violence (GBV) from what lay people think about the issue by conducting text analysis from research articles and Twitter users. The second group project focused on measuring depression and stress-related issues by analyzing tweets in South Africa. They considered three sets of people; those who tweet about depression and have experienced it (Treatment Group), those who just tweet about it (Control Group 1) and those who didn’t tweet about it (Control group 2). The prevalence of depression among control group 1 was then predicted by comparing their characteristics with those of the treatment group. The third group worked to understand the environment of published news in South Africa. To do this, they analyzed publishers’ social Twitter network, and tweets from a topic and network analysis perspective. Finally, two other groups took an usual social science research approach to working on divorce and school dropouts in South Africa, based on panel data from the NIDS. They combined traditional statistical approaches with machine learning to better understand and predict these outcomes. These research projects should continue after the end of the workshop, and we hope to publish their findings in a special edition of the African Population Studies journal.

For many participants, this summer institute constituted both their first use of the R Software and their introduction to digital trace data methodologies. This proved to be a challenge for several participants, and for next year’s Summer Institute workshop, we plan to notify the participants much earlier of their admission, so as to permit them to get up to speed prior to the workshop by taking recommended online courses. We hope also that several participants will start using R in their own courses, making it easier for their best students to enroll in next year’s Summer Institute workshop. This summer institute has been a real opportunity for establishing new collaborations for many participants. The group project work developed during the second week proved to be an extraordinary and successful experience. There are no other opportunities offered elsewhere on the continent on the analysis of digital trace data. The success of the Summer Institute is obvious as the unsolicited comments we received and the final evaluation of the training. About 85% of the participants responded to that survey that they will definitely advise others to apply for the Summer Institute next year. Almost all of the participants also expressed their intention to make use in future of the methodologies learned during the Summer Institute.

A final source of satisfaction is to bring many scholars from outside Cape Town and to give opportunities to Master and PhD students together to attend the Summer Institute. Half of the 26 participants of the Summer Institute came from outside Cape Town, with foreign participants coming from 9 countries in both French-speaking countries (Benin, Burkina Faso and Togo) and English-speaking countries (Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, Swaziland, Uganda, UK). This was made possible in large part by financial support provided by the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP). In addition, as the participants came from diverse disciplines, the workshop allowed participants the opportunity to exchange with others on issues of common interest and thus to break down disciplinary boundaries.

[1] Vissého Adjiwanou is now Professor (Professeur régulier) at the Université de Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and appointed as an Adjunct Senior Lecturer at the University of Cape Town.

University of Colorado (organizers: Brian Keegan and Allison Morgan)

The Summer Institute in Computational Social Science at the University of Colorado, Boulder ran from August 13th through 17th, and was organized by Brian Keegan and Allie Morgan. In addition to our sponsorship from the Russell Sage and Sloan foundations, we received support from the Center to Advance Research and Training in the Social Sciences (CARTSS), Institute of Behavioral Science (IBS), and Center for Research Data and Digital Scholarship (CRDDS). Our satellite operated later than the six other satellites, which gave us the opportunity to build and slightly adapt the materials presented at the primary SICSS. However, we remained very much in keeping with the five overall goals of the program:

(1 & 2) “Challenge disciplinary divides” & “Reach a broad audience”

Nineteen of our thirty-one participants were from the University of Colorado, with twelve coming from universities across the U.S. and Canada, and over 60% of our participants identifying as female. We spanned nineteen disciplines: political science, sociology, computer and information science, history, archaeology, criminology, nursing, education, and others. Presentations from our guest speakers touched on computational social science research across many of the fields mentioned above.

(3) “Open-source”

All of the materials for our satellite, including our guest speakers’ presentations, can be found on our website. Additionally, we live-streamed all of our lectures during the program. The availability of these materials was routinely positively mentioned on daily surveys administered throughout the program, and was ranked by some as the most important part of the program. In the future, like the primary SICSS site, we would also like to record our lectures for future playback.

(4) “Teach the teachers”

Last year’s SICSS inspired many alumni to bring the program to their institutions across the world. Through last year’s instruction, and with the commitments of Matt and Chris to open-source their teaching materials, Allie lead a technical lecture on web scraping, helped facilitate two network science group activities, and lead several group discussions. So with respect to teaching the teachers, last year’s program has been a great success. Among our participants at CU this year, five were early career faculty or postdocs, with the rest being PhD students at various stages in their programs. Time will tell whether our satellite will inspire participants to teach this material at their departments and institutions, but the overall positive response from our satellite is an encouraging sign.

(5) “Provide state-of-the-art training”

Lectures were led by local experts, and touched on details of computational social science methods, as well as applications to current research. The general response from our participants was that the lectures were very informative and provided new methods helpful to their research. After leaving SICSS, our participants expressed a strong desire to continue working in computational social science, and many indicated they would encourage others to apply to future versions.

In this short summary of our satellite, we now plan to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of our program in the format of our daily surveys (“keep”, “stop”, “start”), and highlight possible ways forward for future SICSS satellites.

Keep – What we did that is worth continuing.

- Interactivity: We adapted our schedule from the primary SICSS program at Duke slightly, so that technical lectures included short, relevant case-studies. This served to separate the dense lectures within a day.

- Open-source: Our participants truly appreciated the availability of materials online for reference after the program. Perhaps one of the most rewarding parts of organizing SICSS, was seeing our students build on top of the Jupyter notebooks we developed for the course with research questions of their own.

- Guest lectures: Our program included seven research talks from early career, CU faculty across information science, network science, computer science, and sociology. Across all five of our daily surveys, one of the most consistent pieces of feedback we received from our participants was that they greatly enjoyed those afternoon guest lectures.

Stop – What we did that is not worth continuing.

- Morning discussion: We allocated too much time at the beginning of our days for group discussion on topics as they related to the day. The goals of these round-robin exercises were three-fold: (1) provide time for participants to fill out daily surveys, (2) address any technical difficulties from the day before and define the software requirements of the day, and primarily, (3) encourage discussion amongst participants.

- Providing more structure to the hour we assigned for these three components would go a long way (e.g., survey for 10, software setup and troubleshooting for 20, and discussion for 30 minutes). Additionally, some of the discussion prompts assumed a background knowledge of the topic being presented that day. We hoped that they would spur questions that would be addressed in the material presented later that day, or would be answered among group members, but perhaps a bit more guidance ahead of the activity would help tremendously.

Start – What we did not do, but should in the future.

- More socializing: We hoped that hanging out might occur organically, so we held just one participant get-together towards the end of SICSS. Several participants mentioned wishing for more unstructured hangout time. We think an opportunity at the beginning of the program, as well as routine evening outings for dinner and drinks, would facilitate a more friendly environment and long-lasting relationships among participants.

- Projects: Several participants mentioned that they would enjoy longer periods of time to collaborate on their own research. Our satellite did not include the second week of the SICSS program for group projects, and it seems as though future versions should incorporate this.

- More technical help: A handful of participants expressed the need for more one-on-one attention while running through the code for the group exercises. In the future, satellites should invest in a TA who could always be roaming the classroom to help students who are stuck. Additionally, we think our satellite could have done a better job informing our students of the software packages we would be using the day of, or (even better) the day before.

University of Helsinki & Aalto University (Matti Nelimarkka)

The Helsinki Context

The SICSS Helsinki partner site was organized in Helsinki, Finland. We organized it as a two-week institute: the first week was focused on lectures and second week on group projects. We had a total of 19 participants, an instructor and two TAs. Participants were both from Finland (University of Helsinki, Aalto University, Tampere University of Technology, Turku University) as well as from other European countries (Netherlands, Poland, Germany, Denmark) and rest of the world (India, Turkey). The overall net promoter score (based on the after-course evaluation) was 9 – indicating that the participants considered the course successful and would recommend it to their colleagues. Similarly, the textual feedback suggested that the course was found helpful, engaging and even fun.

Group dynamics

We had made a deliberate decision at Helsinki to take the student group to an offsite location for the first week in Tvärminne. Beyond providing a fabulous venue in terms of scenery, outdoor activities and food, it also forced participants to have an on-campus experience for the first week, and socialize. Based on my random observations, this seemed to be happening during evenings, after the classes. Similarly, we chosen to organize after work activities during the second week, which aimed to help mitigating some of the challenges of lack of residential accommodation and social activities which emerges from that collocation.

What I found challenging and surprising was the need to facilitate group processes during the second week focused on group work. This was not extensive, and rather often groups seemed to manage on their own with this. We were rather pressed for time during the second week, but I’m thinking should we organize dailies similar to agile software production: each team member would speak for a few minutes what they are doing next, what have they done and if they have any major challenges. It might help us to intervene quicker in the group processes facilitation to potential problems and help the groups to manage the time and workload of such short project. Ideally, over the week, we should move the responsibility of organizing these dailies to the groups.

Something I was disappointed myself was lack of a “global” community of SICSS in the course Slack community. I believe that majority of comments from Helsinki to the public channel came from me or our TAs. Reasons for this may include time difference between Europe and US – but maybe also some failures to motivate and incentive this correctly by my side. Maybe next year, the Slack community management could consider establishing smaller channels for particular topics (“communities of practices”) to help people finding smaller venues where they can collaborate and share ideas and comments. Another aspect which I think might be helpful would be to start the online community building way before the event, also content wise. For example, maybe we could create for some of the pre-readings cross-national reading groups or other activities which would encourage them to speak with people from other communities?

Instruction and activities during first week

Something we spend a lot of time discussing with my TAs (in our debrief after SICSS) was the scope of the instruction. We covered many different things during the first week to provide a general overview of several different method families in computational social science. However, the question was if there should be more extensive discussion about some methods to ensure that students are able to fully understand them and not just rush through them. It was even proposed that we should really go through some basics of algorithms and computer science for the students.

However, I believe that the current idea of providing a rich overview of different methods is a good choice. It will familiarize students with many opportunities and help them to rethink social research. However, this is a communication challenge: this type of pedagogical choice needs to be explained and articulated. I did a few rounds of talks focused on this topic, but having that mentioned already on day one would be nice. (For example, one student commented in the feedback form that we could have a separate institute on any of these topics – which is true – and thus indicating that we should have been much more clear on the scope and idea behind that scope).

Second aspect which we discussed with my TAs and some participants explicitly commented: the course was a good crash course for people entering computational social science from a social science background, but for people coming from computer sciences and familiar with data science things many aspects of these lectures were rather boring and even useless. We tried to introduce to some activities (ad hoc) refocus on aspects such as teaching qualitative research methods to those not familiar with them or directing them to consider social science theory of their data analysis. These types of aspects could be more baked into the activities material next year (and I’m happy to help editing them towards this goal).

I will discuss video lectures later, but we had a mix of content coming from Helsinki (i.e., I was instructing the content) and some parts we choose to take as video lectures. Something I found difficult when instructing was to find the correct balance between audience participation and me lecturing topics. (To be honest, I actually don’t usually enjoy lecturing that much.) In some of my regular computational social science classes at University of Helsinki, I usually ask students to read a case study before the class which applies the approach or method we are learning. It serves two aspects: first, we can use that article to develop fruitful discussions with the students and therefore, I don’t need to lecture as much. Second and more importantly, the case studies provide the students an opportunity to see how “social science theory” (whatever that means) is integrated in the computational work – which I also believe to be a core skill in computational social sciences. If I’m organizing a class like this next year, I would integrate a component like this to balance the me-speaking – students-speaking a bit.

The video lectures

Overall, given the time difference organizing the video lectures was somewhat challenging. For the guest lectures (given at Duke in the evening) we opted to watch them delayed the next day. This reduced some aspects of their liveliness, which many students commented in somewhat negative tone. We tried to stop these lectures when possible to discuss the lectures in our group (a proposal by one of the students) and this seemed to make them somewhat more engaging. I would recommend similar idea to other locations which must follow lectures in non-live format.

On the instruction (given at Duke during morning), we chose some topics where we followed the Duke stream while on other topics I chosen to held the lectures myself. The student feedback suggested that they liked these locally provided lectures more than following live streams from Duke, so I think we made the right decision to develop some instruction on our own. Naturally the challenge with this is that the quality and content between the institutes may vary somewhat (for example, for text analysis, I chose to start the lecture by speaking about traditional qualitative research methods). However, I think that some quality bonus we had from organizing these locally – such as high level of interactivity and ability to react to local situations – was worth of this extra investment. In future years, I would examine to replace even more of these lectures when possible and to support on that, produce the materials early enough to allow discussions of them within the instructor community to find potential areas of improvements.

The project week

My only concerns which emerged from the project week related to the group dynamics and lack of proper theoretical reflections during them. I think our group creation process could have been clearer for people; we asked everyone to list topics they find interesting and in collaborative manner, mark which of them they might consider working on. Initial groups were formed based on that and even while I tried to encourage participants to not stay in what seemed like the local optimum, these groupings were set. I think next time, I would force people to change the groups and have similar discussions once or twice to show them the range of opportunities. Furthermore, facilitation of the project management as discussed above may have helped in this. Similarly, on the theoretical reflection, I did ask people to produce a mind map on the first day about theoretical concepts and literature and relationship between those and what they planned to do. Sadly, this itself did not seem to help students enough to engage in this thinking and follow that throughout the week. Again, scaffolding and facilitation may provide helpful in this.

Facilities

While the first week facilities were excellent, the second week facilities were in our use daily only from 8am to 4pm. This limited some activities and influenced our scheduling. As the summer institute is during summer, many spaces at University of Helsinki just closed a bit too early. Next year, I would reconsider the second week location to have a few more hours of shared time. Also, I would have a clear single location for all non-Helsinki visitors and recommend they stay there to reduce some extra coordination efforts.

Negotiating interdisciplinary and cultural boundaries

Something I tried to bring you in fishbowl discussions was the interdisciplinary nature of computational social science and some of the challenges and problems related to this. Sadly, while I enjoyed these discussions, their intention may not have been as clear for participants as it was to me. I have been working across different academic communities for a long time and thus, rather familiar in interdisciplinary collaborations. They take time and often require a lot of flexibility and openness. However, I think that I understand the difficulties of these jumps as I’m so familiar with them and thus, didn’t provide as much support as one could have provided during the two weeks. For example, the fact that I rarely addressed traditional social science theories and methods in the instruction could have helped participants to follow the teaching more and made the classes more engaging to people from computer science background as well.

Similarly, the problem with teaching interdisciplinary groups is their internal heterogeneity in terms of skills. One solution worth of consideration could be to separate the group based on skills or provide even more modular learning activities, where we could assign different participants and groups slight variations of the same tasks to make them more engaging or to allow participants to enter zone of proximal development. This again would most likely push us to reconsider the role of lectures and instruction.

Finally, people did come from different cultures (not only country wise, but also academic cultures), which meant that their understandings of – among other things – research contributions, value of group work and ideas of good instruction differed. These were not something major challenges in the project. However, for me better managing this boundary work in the future is critical and having tools and approaches to facilitate students with these is necessarily. Sadly, I don’t yet have a clear and good solution for this problem.

Conclusion

The aim of this reflection has been to pinpoint potential areas for improvement, both for myself as well as other SICSS communities and their organization. Therefore, I have aimed to address challenges and problems and discuss them in extensive manner. However, as said in the beginning, most participants had a positive and engaging experience with this summer institute. The ideas and comments throughout this text may help to further improve the learning and clarify some of the difficulties observed.

We thank support from Russell Sage Foundation, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Helsinki Institute for Information Technology HIIT for their generous financial support.

University of Washington (Connor Gilroy and Bernease Herman)

The participants

The core of the Seattle partner location for SICSS, and the key to its success this year, was our set of 23 participants. These participants came from all stages in their academic careers: 2 Masters students (9%), 14 PhD students (61%), 2 postdocs (9%), and 5 faculty (22%). While many of the postdoctoral fellows and graduate students had some exposure to computational social science, we found a general trend: faculty often applied to SICSS-Seattle with less hands-on experience with computational methods but expressed great enthusiasm to gain exposure to computational methods, apply to research, and share with their students.